Not Quite

Teddy, Thalia, and I are all secure in the comfy chair; the light from the fireplace sends flickering shadows onto the blanket covering our legs. In our erratic progression through Grimms’ collection of over two hundred fairy tales, we have landed upon Foundling.

A forester, out hunting, hears the sound of a child crying. After a puzzling search, he finds the child in the top boughs of a tree. The story tells us that a hawk stole the child from the lap of his sleeping mother and left him on a tree top. The forester rescues the little lad and decides to raise him with his own daughter, Lena. Because he found the child, the forester names him Foundling.

As the two children grow, they become exceedingly fond of each other. If they are not together they soon become sad. One day Lena sees the old cook, Sanna, carrying a great number of water buckets into the kitchen. She asks Sanna why she does so, and Sanna, after making Lena promise to tell no one, confides that she intends to cook Foundling in the morning after the forester goes out hunting.

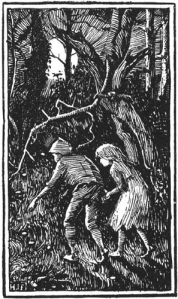

Early the next morning Lena tells Foundling, “If you won’t forsake me, I won’t forsake you.” To which Foundling replies, “Never ever.” That becomes a refrain throughout the rest of the story. Breaking her promise to Sanna, Lena tells Foundling of his plight, and they run off together.

When Sanna finds that both children are gone, she sends three servants to bring them back. Lena sees them from afar. She tells Foundling to turn himself into a rose tree; she becomes a rosebud upon that tree. When the servants come to where the children were, but cannot find them, they return to the cook, telling her that all they found was a rose tree.

Enraged, the cook sends the servants back to cut down the rose tree and bring her the rosebud. Again, Lena sees them coming, and this time the servants find a church—Foundling—and inside nothing but a chandelier—Lena.

Thwarted again, the cook accompanies the three servants to accomplish the task. Lena tells Foundling to turn into a pond; she turns into a duck swimming on the pond. Seeing this, the cook kneels down and begins to drink up the pond. Quickly, Lena grabs the cook’s head in her beak and pulls her underwater, drowning the old woman. It is in this last moment that the story reveals the cook as a witch.

Lena and Foundling return home.

“Teddy and I don’t like that story.” Thalia is pouting.

“Why? What’s wrong with it?”

“It’s dumb. Read the next one.”

“The next one is King Thrushbeard. We’ve read that already.”

“Goody. Read it again.”

And so I do.

I find “dumb” an insufficient analysis. The tale has the basic fairy-tale components: a beginning, middle, and end (This is not to be taken for granted.); a protagonist (two actually); a villain; lots of magic; and a happy ending.

And yet, Thalia is right. There is something about this tale that does not quite satisfy.

Fairy Tale of the Month: February 2015 Foundling – Part Two

Evil for Evil’s Sake

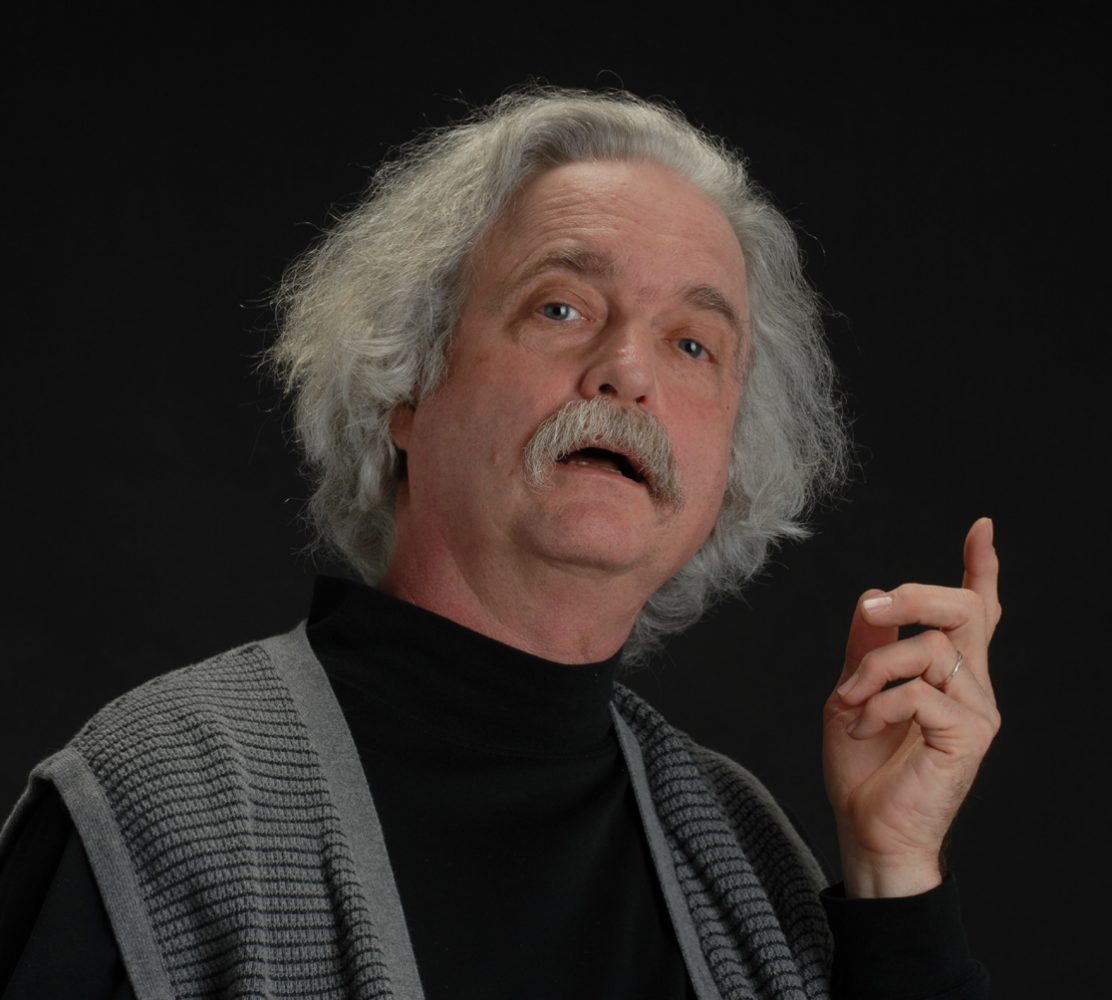

“Foundling. Foundling.” Augustus’ eyebrows knit. He rises from the overstuffed chair and stands before his bookshelves, which are lined with notebooks.

I had gotten here just as he closed the shop for the day, and we tucked ourselves away in his study for a visit. Augustus pulls a notebook from a shelf, peruses it, replaces it, and picks another. I know he is a self-taught scholar, and claims to have come up with a tale-classification system simpler and more scientific that Aarne-Thompson’s. He explained it to me once until I became completely befuddled.

“Ah, here, yes. I recall it now.” He sits down with a binder in his lap. “I have it in my notes as ‘a failed tale.’ ”

“How unkind,” I say.

“I am afraid this tale suffers from Wilhelmitis.

“Pardon? I think you are coining a word.”

Augustus smiles. “I have two arguments to justify that statement. Starting with a minor point, Lena promises the cook she would not tell anyone of what was about to be said. Lena breaks that promise by warning Foundling of his impending doom.

“That’s excusable in the real world, but in the fairy-tale realm that cannot be done without dire consequences. Promises, however ill-advised in their making, are binding. For Lena there are no consequences. That is a clear violation of fairy-tale law.

“More pertinent to my argument, the Grimms’ stories’ popularity and longevity have to do with the literary polish the brothers—particularly Wilhelm—worked upon them. However, there were casualties and this tale is one of them.”

Augustus pages through his notes before continuing. “Because they wanted to appeal to a middle class audience—and note this was an evolving middle class caught between the minions of the old Holy Roman Empire and the rabble of the German nationalistic movements—Wilhelm quickly made changes to the stories to satisfy their tastes.

“In the original 1812 version, the foundling is a girl baby whom the forester names Birdie. Putting myself in Wilhelm’s shoes, I think he made the change from a female foundling to a male foundling simply to conform to the popularity of the fond-brother-and-sister theme

“A bigger problem for Wilhelm was that in at least one version of the collected tales the villain was not the cook, but the forester’s wife, who wanted to cook the intruding foundling.

“The motive for the wife’s action is easy to imagine; that she would confide in her own daughter makes more sense than the cook confiding in Lena, but Wilhelm faced having the daughter kill her own mother to save the foundling. He apparently didn’t think that would fly with his audience. The usual solution of substituting an evil stepmother now gets complicated with a new wife, stepdaughter, and adopted daughter. Wilhelm solves the problem by turning the wife into an old cook.”

“Ah,” I say, “but she is a villain with no motive. That is what Thalia sensed. The cook is evil for no reason. Now that is unsettling.”

Your thoughts?

Fairy Tale of the Month: February 2015 Foundling – Part Three

Holding Magic

Our resident fairy is curled up and sleeping on Thalia’s copy of Grimm, which lies open to the Foundling; her black hair, filled with static electricity floats about her, moving and swirling with her breathing. I sit as close as I dare, contemplating the delicacy of her fey nature. Her beauty is that she is not common.

My “failed fairy tale” as Augustus calls it, has plenty of fairy-like magic in it. In the Foundlingthe children turn themselves into a rose tree, a rosebud, a church, a chandelier, a pond, and a duck. Not too shabby, but they have broken with acceptable decorum.

Mistakenly, some who imbibe story liquor allow that anything can happen in a fairy tale. Well, they are drunk. Fairy tales, in their own way, are stodgy teetotalers, walking a straight line of convention. The faux pas that the Foundling commits is granting commoners (Lena and Foundling) the power to transform themselves into other shapes, that is to say, possess magic.

No one has written the etiquette book for fairy tales but, if someone had, it would clearly state that commoners are not inherently magical. Magic is in the hands of witches, wizards (who rarely appear in the Grimm canon), fey beings, and royalty. This breakdown of who has magic fascinates me.

That fey beings, such as fairies, dwarves, and demons, have magic is a given. They are a class of beings all unto themselves.

Witches, however, are human. With a few exceptions, they are old, ugly, and poor. More accurately, they appear to be poor. Witches may have amassed wealth in the cellars and tunnels under their humble abodes. Still, even a gingerbread house does not rise to the level of a castle. In the Celtic tradition it is the henwife, poorest of the poor, who practices the uncanny arts.

At the other end of the medieval economic spectrum, royalty, by birth apparently, also hold magic. In the Goose Girl the elderly queen gives her daughter a protective token (three drops of blood on a handkerchief) and the talking horse, Falada. The young princess talks to the beheaded horse and raises winds to blow off the cap of an annoying little boy. The tale feels no need to explain these things. That the queen and the princess possess magic is as much a given as the fey beings having these skills.

The only magic commoners should have are those mysterious items given to them by magical helpers (old women in the wood, or little old men the protagonists chance to meet).

Quietly I tamp and light my pipe. The fairy opens one eye, but then slips off to sleep again. I am pleased she is not disturbed by my presence.

Magic is not common. It exists at the far ends of fairy-tale society, among poor old women, those privileged by birth, and the fey. Magic for the commoners should be doled out sparingly, a cloak of invisibility here, a magic sack there, and no more than three wishes at a time.

Watching the sleeping fairy, I resist the urge to pick her up and hold her in my hand. After all, she is magic and I a commoner.

Your thoughts?